The Forgotten Man video walkthrough incorporates an in depth conversational exploration with viewers, delves into the personal history behind this project, and invites viewers to reflect on the hidden stories that lie within their own ancestry.

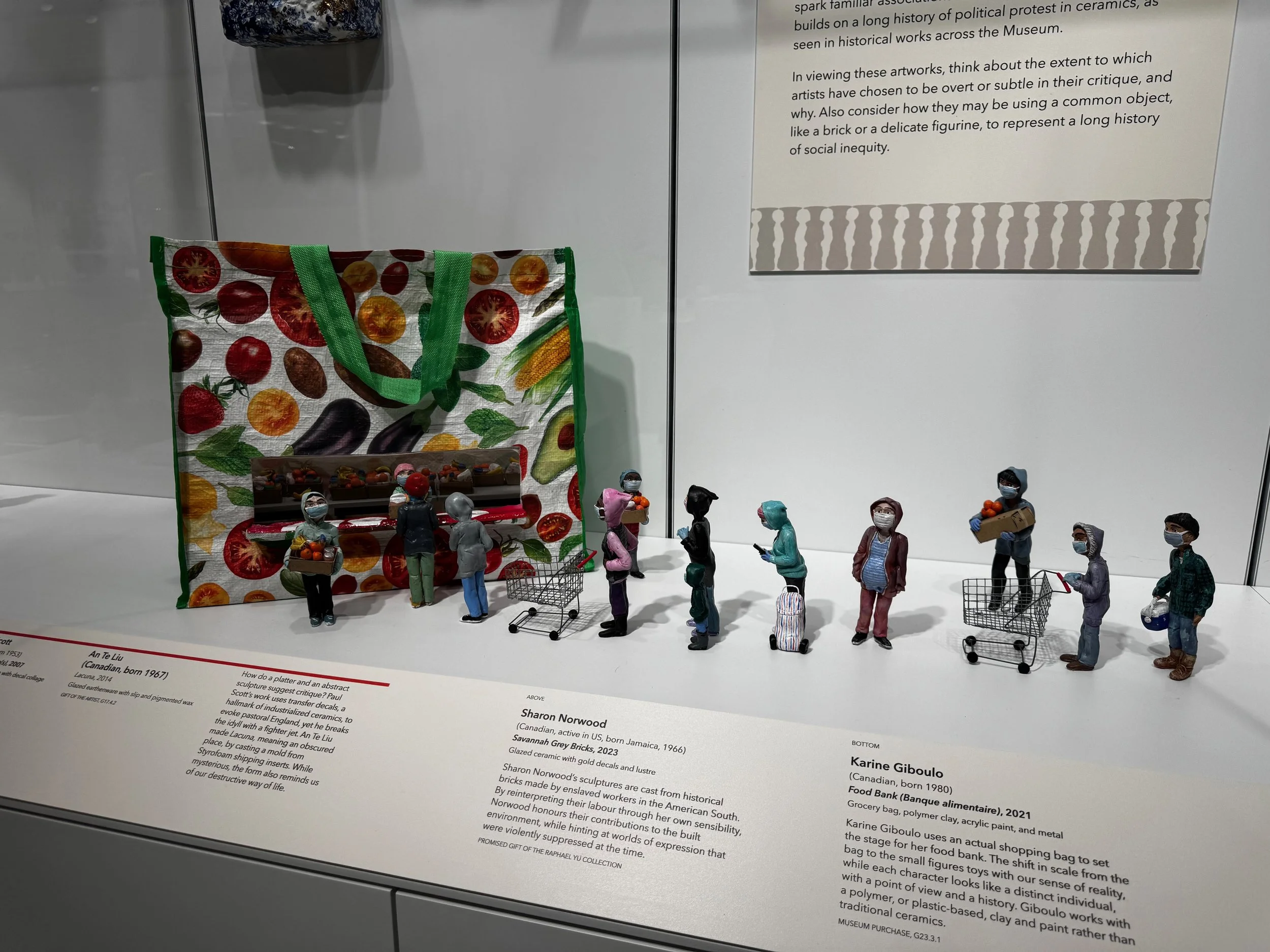

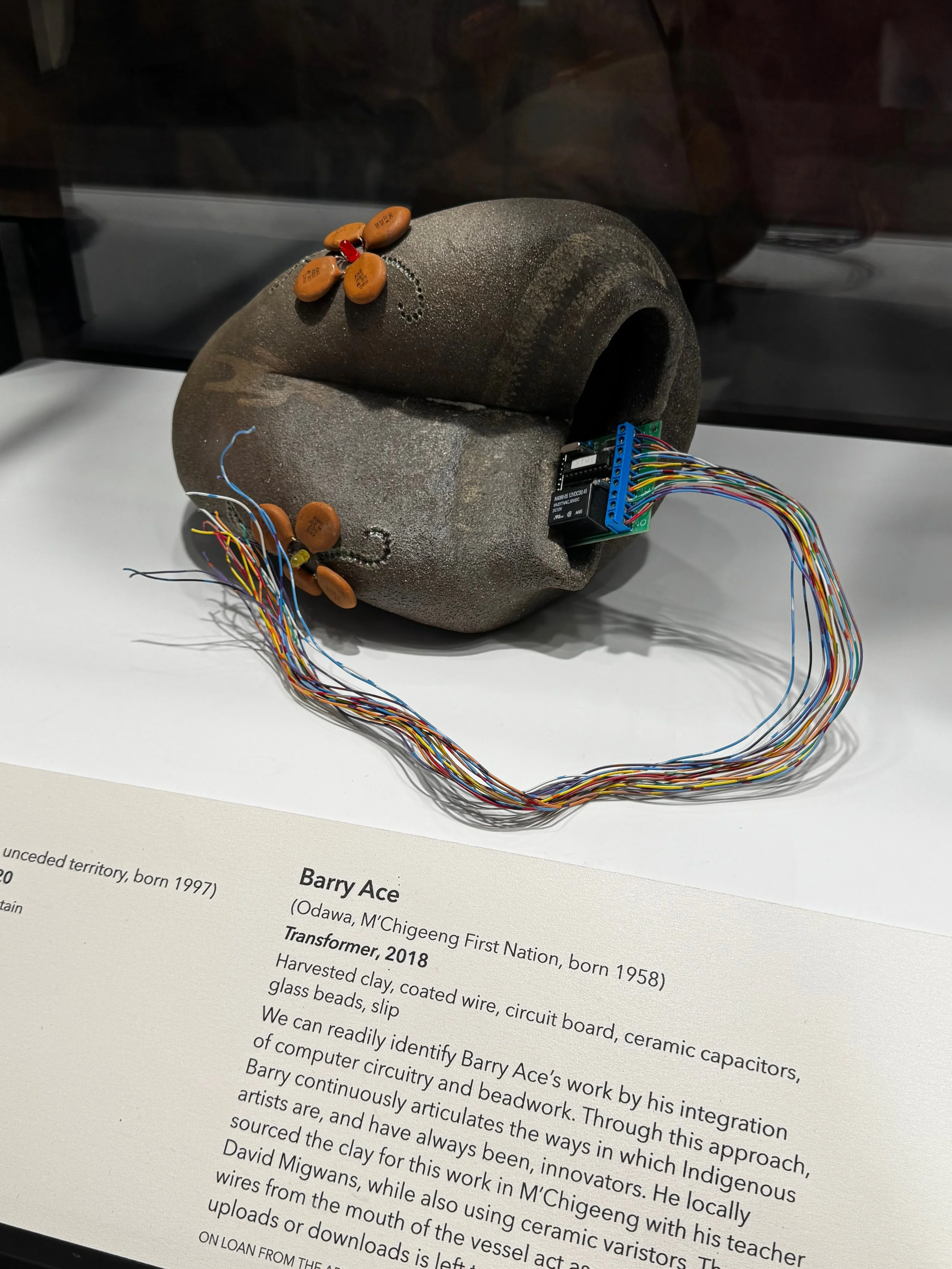

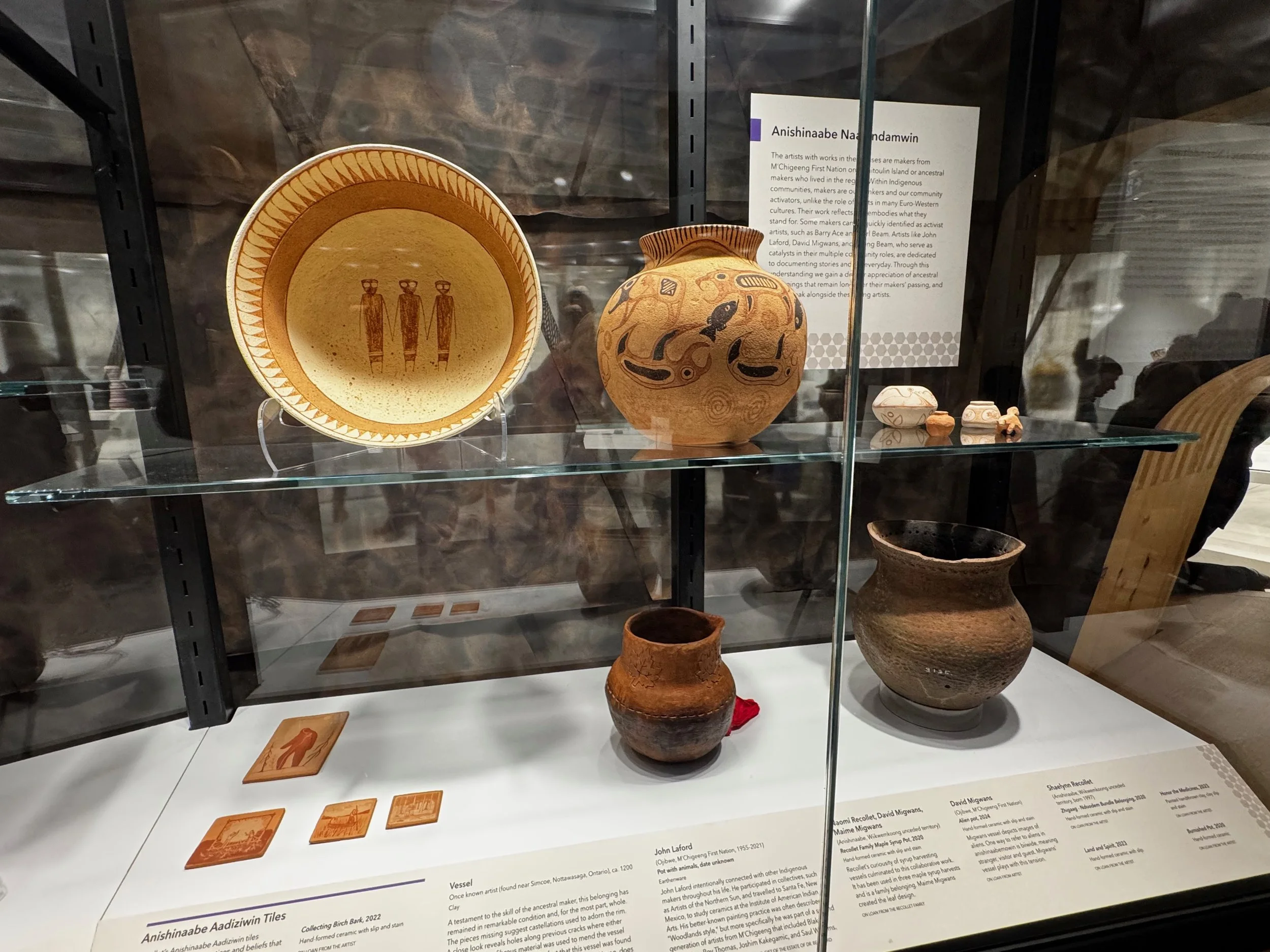

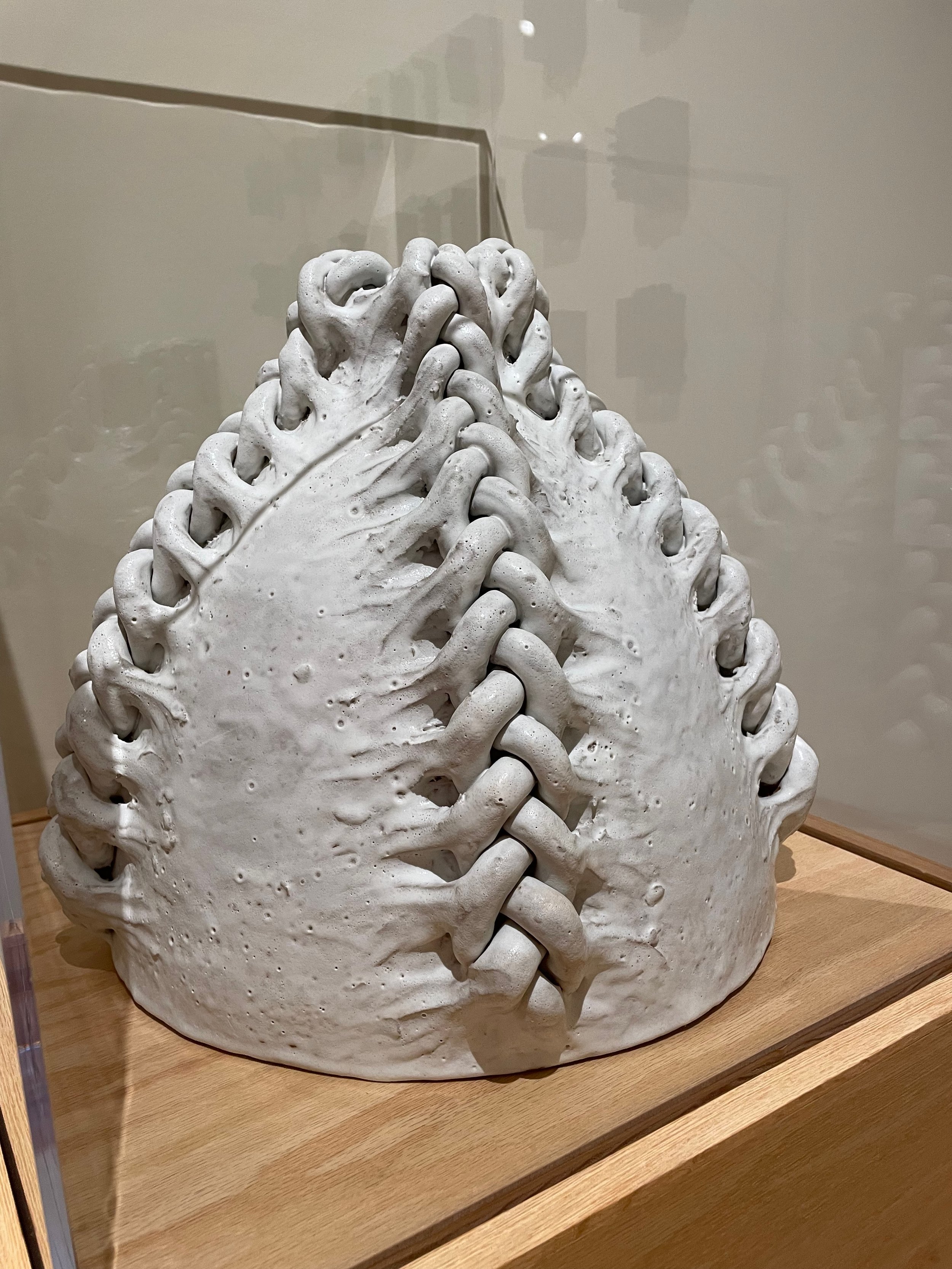

Gardiner Museum Opens with Building Blocks

I’m so thrilled that Sequoia Miller and the Acquisitions Committee at the Gardiner Museum chose to acquire Building Blocks and have re-opened their newly designed first floor galleries with this work in the cases alongside so many amazing artists!!!!

La Galerie de Ceramique Contemporain, Centre de Ceramique Bonsecours, 444 Rue Saint-Gabriel, Montreal

L'Homme Oublie / The Forgotten Man - Montreal

The Forgotten Man, solo multi-media installation about my reckoning with my father’s support for the white Biology professor who’s academic racism caused the largest race riots in Canadian history in February 1969.

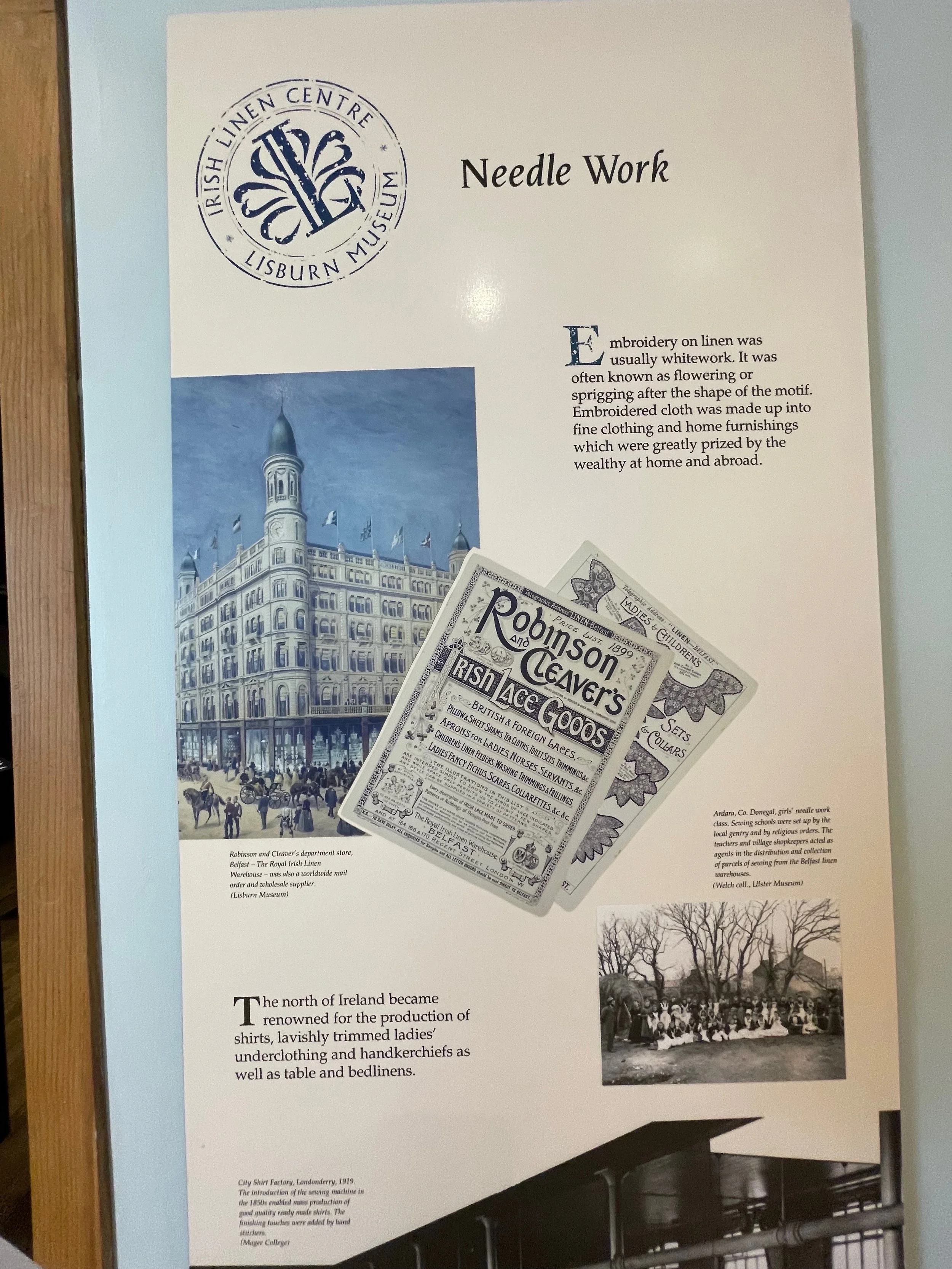

Read MoreMissive - Belfast Linen Biennale September 2025

Belfast teams with energy and possibility. I feel totally sympatico with this city. I feel like the pink double-decker buses were painted just for me. Pink has been my core colour since I bartered with a design firm when I was a consultant and they told me that hot pink was “who I was” and I realized they were right. It’s strong and bold, feminine but not fragile. When the man with the orange rug on his head (who shall not be named) was elected, I decided that bright colours would be my form of protest, a counter move to the darkness in the world. Belfast has bright bold colours nearly everywhere you look – even in the bathrooms!

I found the light entrancing. The mystery in the sky is ever-changing and changeable. I stopped to consider the way the light fell on buildings and snapped away on my iPhone, trying to capture the essence of this place. People don’t seem to take head when the clouds burst and there is a sudden rain shower, they just keep walking. After a couple of days, I found myself leaving my umbrella in its bag, knowing with confidence that the sun was just around the corner.

I went to Belfast partly on a reconnaissance mission, to find future fits and folks for as yet unimagined projects, and partly to mark my participation in the Linen Biennale Norther Ireland.

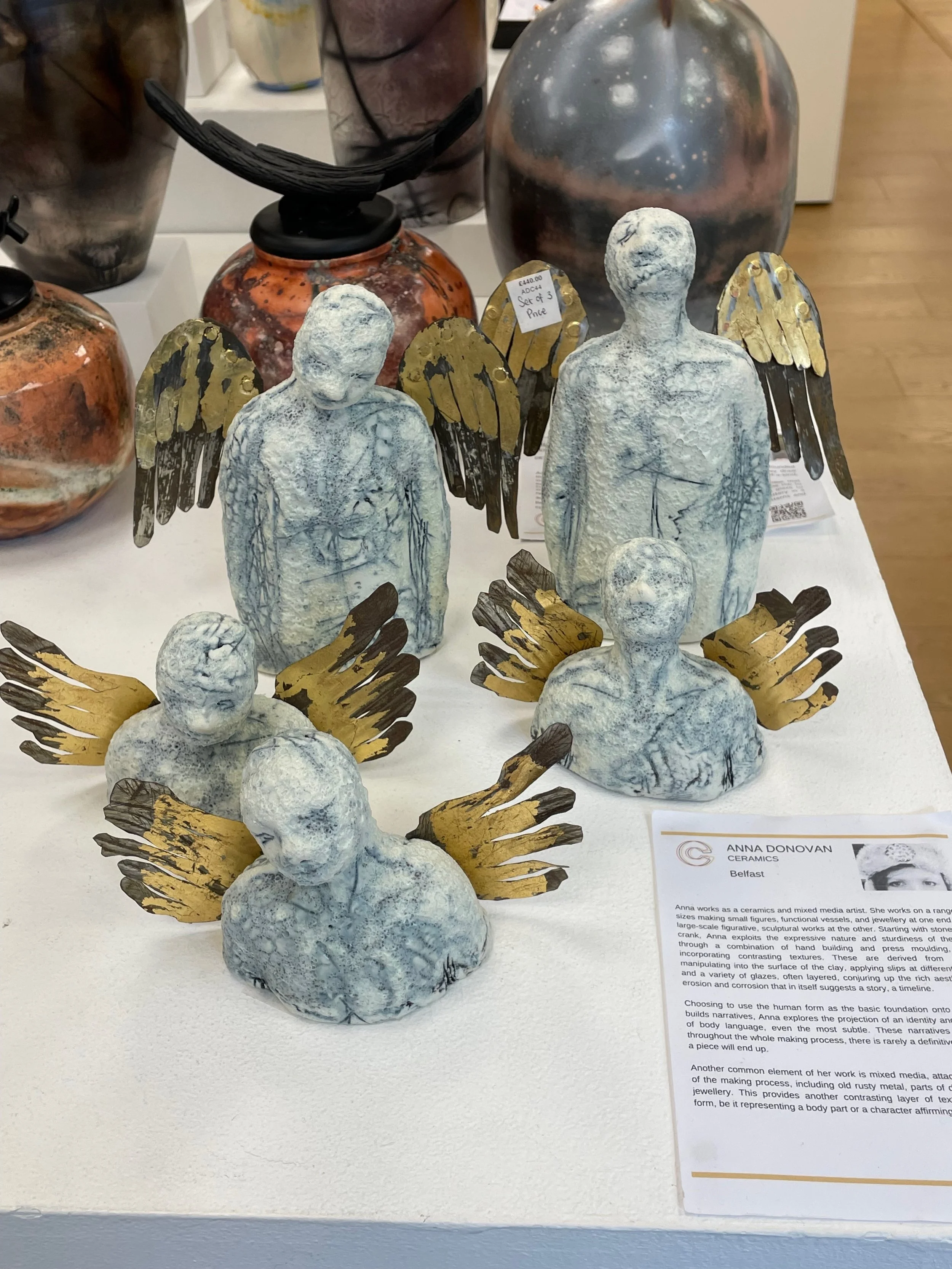

Tragically, UPS held onto my sculpture until the day I left, the day before the show closed. Meadhb (pronounced Maeve) curated Common Threads. She’s a warm and spritely 30-something independent curator, artist and arts manager. Meadhb hosted me, showed me around the East End of Belfast, that boats multiple mixed art/commercial complexes that have taken over the shells of old factories or mills – reminiscent of the Distillery District in Toronto’s East end. I had a meaningful and memorable studio visit with Derek Wilson, who shared openly about his creative process and took me to his “secret room” where he’s working with cardboard and paper collage, reflecting on the ceramic work he is known for internationally. I dropped by Belfast Ceramics, the first and only drop-in/membership based community pottery studio in the city – odd that, there is much demand, just as there is for the many many pottery places that mushroomed during/post COVID in Toronto. Helen and her tech Lucy and I had a great exchange of ideas and process, career challenges and hurdles.

I “did” the museum and contemporary gallery circuit, buried my nose in Belfast’s last subscription library, Linen Hall, and partook of a guided tour of City Hall. I returned to the Lisburn Irish Linen Museum that Ali had spontaneously taken us to as a detour two years ago. I met with fellow ceramic artists in the community and the museums’ curator. I gave my artist talk at the civic arts complex. It’s a tiny walkable town that oozes charm. The calibre of the international exhibition that Meadbh put together is more than impressive – I was completely drawn in, somewhat spellbound by much of the work. And I’m home, turning my head to completing the solo show that’s opening in Montreal on October 23rd around the race protests of 1969, and my father’s character witness of the accused white Biology professor who catalyzed the whole international incident.

thanks to the Ontario Arts Council for the Market Development Grant

MISSIVE: NCECA SYMPOSIA IN NANTUCKET - A GIFT!

Missive re Nantucket Island School of Design & the Arts

I’m still basking in the glow of my week on Nantucket, tucked away in a massive studio barn with some NCECA peeps and a couple of new mug slinger friends. (National Council for the Education of Ceramic Arts – I’m on the volunteer working board of this organization through which this opportunity came about).

I used the time and space to play, and begin to bring concept to clay with the still life series I’m planning for the Montreal solo show this September. I had brought moulds to get out of the gate running, and little tubs of different possible inclusions to enhance the gritty surface textures I am going for. Serendipity prevailed, and the quality of the tile crushed pebbles/gravel in the sand on the beach at the end of the road need the studio proved to be the most conducive – stunning. I travelled with a small Rubbermaid container of this in my backpack, and twice had security do some extravagant fenagled test on it – apparently they were testing for explosives – but they were happy to let me have a piece of the island.

I have to admit that I also carried a small sampling of scallop shells home, hoping to make earrings for my friends. The abundance of these shells on the beach is immeasurable. Drinking in the fresh Atlantic Sea air brought me right back to summers in my youth at Kouchibouguac, New Brunswick. Tracing a collage of sandprints on the beach with my tai chi remains a favourite privilege and joy.

Steve Hilton, the incoming President of NCECA was our fearless and incredibly helpful leader, and Yesha Panchal, Grace Han, Alex Ferrente, and Stephanie Lanter were part of our talented group. We had an outing to Long Point – bouncing along the beach in the back of a pick up truck, and tumbling out to explore the dunes that bourgeoned with wild rose and fluffy baby sea gulls. The ocean was azure blue and ice cold, but the seals were just as curious about us as we were of them, and they frolicked nearby, peering at us as if we were the main attraction. The excursion ended in an unexpected team building experience when we took the interior road back, and got seriously stuck in the sand. After digging ourselves and pushing and grunting for a while, uner the relentless hot sun – we sent two parties out in two different directions in search of help. Mitch and I eventually flagged down a friendly ranger who saved the day.

The crew of young residents were shy at first, but once we got them to strut their stuff, we felt like a team, and ended the week with twelve wheels spinning, 24 hands creating pots for the Empty Bowls charity.

Laura and Mitch are the summer resident couple who basically make things happen – Laura is the Director of Programming and Mitch makes things happen, along with his trusted furry buddy, Buddha. Mary Kuhn is the magic maker who envisioned and realized the arts centre oasis. We had artist talks, Pecha Kucha style and 15 or so community members came out, and we each had a piece in the small gallery. One community member, invited us to her home with her friends and we got to take in the charm, wit, beauty, and honestness and hospitality of the spirit of Nantucket.

A highlight for me was the Whalers’ Museum that I visited when we spent an afternoon wandering the city itself. The hydrangea are too beautiful for words, and the majority of the homes conform to a grey and white palette, mostly cedar shingles. I happened into a guided visual presentation of the history of not only the island, but the relationship between the Indigenous peoples, the W, and the settlers – it was the Wampanoag People who taught the white man to salvage and efficiently harvest the whales who washed up on the shore. It was the white man who got greedy and started to hunt the whales out of the water. Nantucket was one of the top five whaling ports in North America.

I would be remiss if I did not to mention the culinary expertise that abounded – chipotle, arepa, dosa, chole/channa, falafel, bibim bap – pretty much an unparalleled global cuisine!

I came away richer for the new and deeper friendships forged, with a fulsome sense of mutual sharing – sharing of ceramic technical and creative tips, sharing of critical feedback, and sharing of our lives. All of the members of the ad-hoc committee re Multicultural Fellows Exhibition Planning happened to be with me – and we engaged in much productive NCECA visioning.

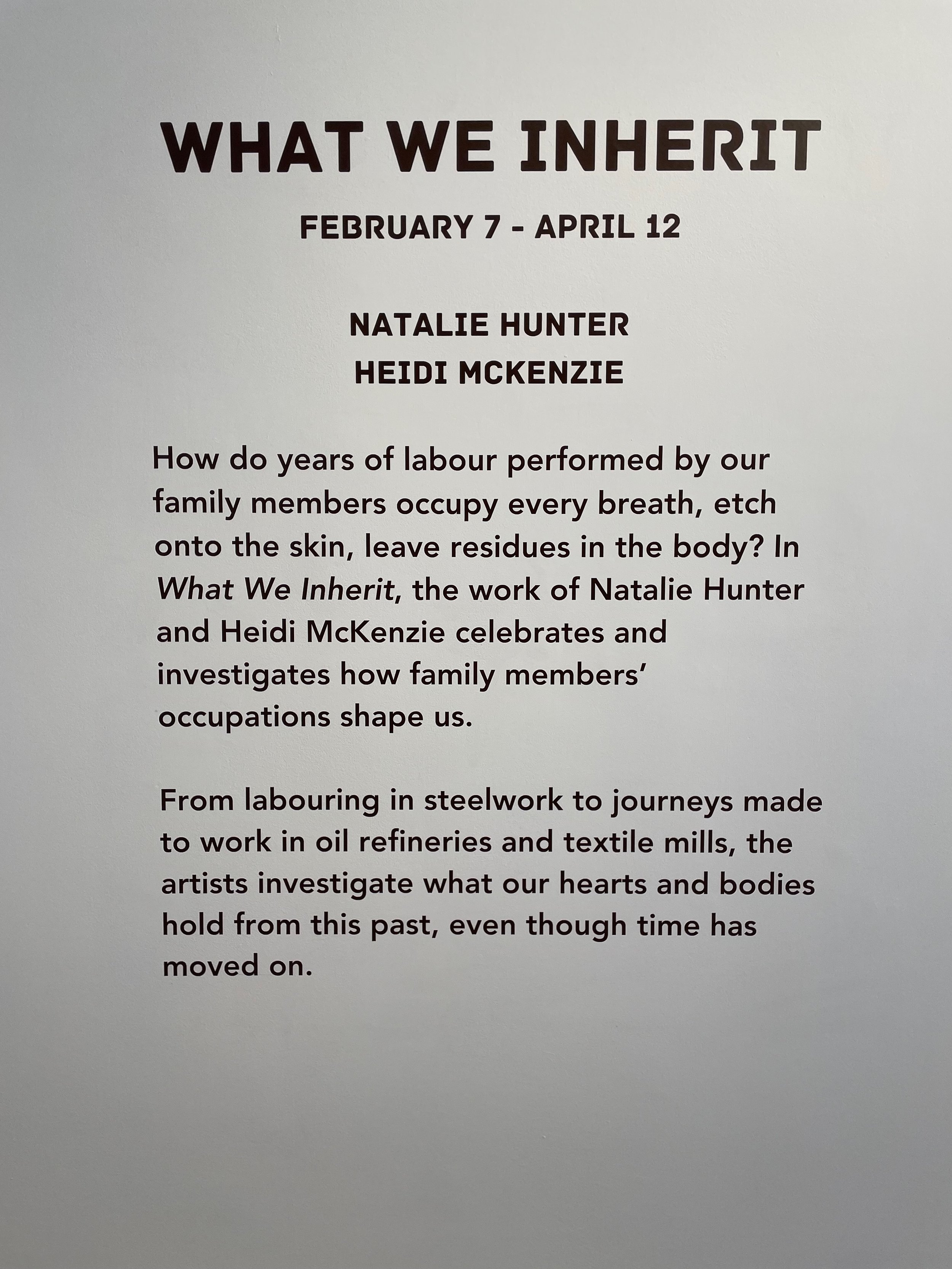

What We Inherit - WAHC

What legacies of labour do we inherit? From pride, activism, and working-class values to injuries, diseases and pollution, the work of Natalie Hunter and Heidi McKenzie in What We Inherit reveals how the legacies of family members’ occupations shape us. Using media that evoke basic elements, the artists ask, how do years of labour performed by our family members occupy every breath, etch onto the skin, leave residues in the body?

Images of structures once populated by workers cast through film celebrate Hunter’s family legacy at Slater Steel and Stelco while mourning the effects of deindustrialization. In earthenware McKenzie explores the impact of work in Trinidad’s oil refinery on her father’s health. Using ceramic tile and video projection McKenzie explores bodily traces of her ancestors who worked their way to Canada from Belfast and India by way of the Caribbean.

Hunter and McKenzie also represent the labour legacy of their maternal lineage in farming, weaving, housework and reproduction using porcelain, ceramic, and photography. Time has moved on, yet what of this work does our heart and body remember?

Speaking Volumes: The Work of Magdalene Odundo

Originally published in October 2024 issue of Ceramics Monthly pages 32-37 . http://www.ceramicsmonthly.org . Copyright, The American Ceramic Society. Reprinted with permission.

Read MoreWatch Curator, Shannon Anderson’s Virtual Tour of the Exhibition Now!

Across Latitudes - Art Gallery of Mississauga

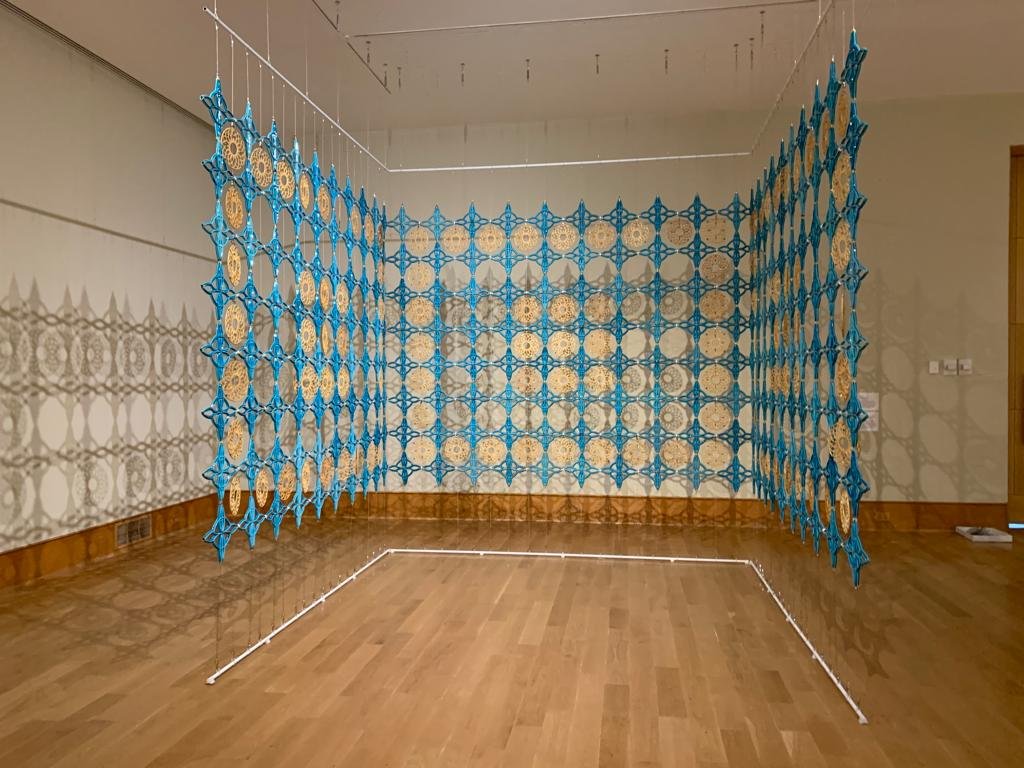

Across Latitudes journeys through the immigrant experiences of Soheila Esfahani, Zinnia Naqvi and Heidi McKenzie. Art Gallery of Mississauga summer 2024

Read MoreUtah

Goblin State Park

The Wonder of Utah - June 2024

I am honoured to serve on the volunteer working Board of NCECA, the National Council for the Education of the Arts. We meet in person three times a year, in June at the location of the following spring’s conference. In 2025, NCECA hosts FORMATION in Salt Lake City Utah. My partner and I took some time to experience this vast corner of the world, which neither of us had seen before. Below are some of the snaps day by day of our 6 day road trip. Food for the soul for any artist!!!!

We spent some time with our dear friend Antra, whom we had met in Bali in 2011 at the Gaya Ceramics residency. She lives North of SLC, and is also a colleague on the board of NCECA. We had a tour of Utah State University’s Ceramic studio and the opportunity to hang out with wood firer extraordinaire, John Neely. The lush landscape was welcome, and unexpected freezing rain storm at the top of the “Caribbean of the Rockies” - Bear Lake. We discovered Minnetonka Caves, some 340 million year old 880-step journey into the soul of a mountain, where the bats were unusually friendly. Stunning -

[Note - you should be able to click on any photo to enlarge and see it full scale]

DAY 1 - Zion National Park, Hilsdale

After the board meetings, we picked up our Kia Kicks and headed out. Zion National Park, our first impressions after the 4.5 hour drive from SLC, was a relative mob-scene with an hour and a half wait to get in. We were troupers in the furnace of the unexpected heat dome and rode the shuttle bus packed like one would imagine the Tokyo subways. We found our zen in the numerous little “off-the-beat-and track” viewpoints and spent the whole day, 2L’s each of water each and rewarded ourselves with some of the best Mexican food I’ve ever had! The shots below with the water are actually of Salt Lake, my guy took off bird watching while we were in meetings.

DAY 2 - Bryce Canyon

We next visited Bryce Canyon, which technically really isn’t a canyon, where the sunset glow of the colours on the 240 million year old sandstone formations in the valley was like watching an animated film over a one and a half hour joyous climb filled with innumerable vistas. The next day we revisited the same sites, completely different visual canvas. This is where I started to understand the ancient rhythms of the geology - ice seeping into the sandstone in harsh winters and splintering the rock formations into “windows” and then these hoodoo like formations.

DAY 3 - Monument Valley, Mexican Hat and The Edge of Cedars State Park and Museum

As its title suggests, these sandstone formations were monumental! We took in Goose Neck State Park in the morning. Completely different geology, dark green, deep, stepped stone down to what is part of the Colorado River. We photographed ourselves on the road with iconic vistas. This is “John Wayne country”. Our non-four-wheel drive KIA Kicks got stuck in the mud of the red sands on the way out of the 17-mile scenic drive, and a Navajo worker on a large tractor came to our rescue. Words are not enough to describe our enchantment. We next motored off to the Edge of the Cedars State Park as it promised had the best and most extensive collection of Pueblo region ceramics - ANYWHERE!!! the Ute, Hopi, Navaho, and Pueblo people and their ruins, painted pots were such an inspiration. We climbed into the Kiva - the underground “pit house” of the indigenous peoples. These people lived in the area from 300AD to 1200AD, then dropped everything and migrated south. Discoveries continue and are recent as the sand still holds so much of their history.

DAY 4 - Arches National Park

We drove onto Moab where we spent two nights. First day resting and taking in the local culture, and hiking the trails of Arches National Park in the evening as the sun set. We learned that the intermittent bright green swaths of landscape were not copper as one might expect, but chlorite and illite. The next day we returned early to Arches, then headed out of the heat towards Canyonlands National Park, and ended our day with an impromptu viewing of a wall of petroglyphs - wondrous and awe-inspiring. The first of many more petroglyphs that we would see on the trip - that are not flagged for tourists as it is assumed the general public are “not that interested” - duh.

DAY 5 - Island in the Sky, Canyonlans, Goblin State Park, Little Wild Horse Slot Canyon

Promised to be 20 degrees cooler, Island in the Skye was a balmy 99F (versus the 112F we had experienced). We started at the highly recommended Goblin Valley. I love the names given to these places, they truly looked like little goblins - thousands of them. We stopped to experience a “slot canyon” Little Wild Horse, where we could trek as far in as we wanted, and return - which for us was a 1.5 hour trip in over 100F. The intimacy and joy of clambering through these narrow cliffs is impossible to relate. We left just in time before a major sandstorm came out of nowhere, and blinded all road visibility.

DAY 6 - Capital Reef National Park

We stayed in a “tiny house” and ate the best authentic Mexican food ever in this tiny town of Torrey the night before we set off on our last day. More petroglyphs, 5000 year old lava boulders strewn amongst 240 million year old sandstone and vistas were stunning. And then we headed back to civilization and very civilized, we rested and took the direct flight home to Toronto. The whole time we kept saying to each other, this is just a reconnaissance trip - we will be back! SO MUCH MORE TO SEE and experience. Beautiful country - near the “four corners” where Colorado, Arizona, Utah and New Mexico meet.

Wind From a Butterfly's Wings: Sculptures in Clay

Heidi McKenzie was the invited international artist in Ahmedabad, India December 15 2023-Jan 30, 2024.

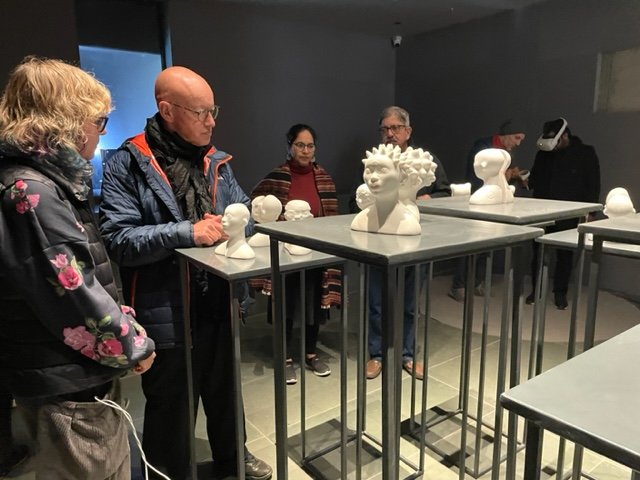

Read MoreCommon Ground, Indian Ceramics Triennale 2024

I was honoured to be invited to exhibit Girmitya Herstories at the Indian Ceramics Triennale with this international group of multi-disciplinary/ceramic artists, all working with the theme of Common Ground, at Delhi’s hottest new gallery, Arthshila. (January 19 - March 31, 2024)

Opening Night Artist Group Photo

Review: From the Other Side

Originally published in October 2024 issue of Ceramics Monthly pages 32-37 . http://www.ceramicsmonthly.org . Copyright, The American Ceramic Society. Reprinted with permission.

Read MoreMaria Gezler Garzuly Workshop - Kecskemét

Missive – Maria Gezler Garzuly Printing on Clay Workshop, Kecskemet, October 2-8 2023

Maria Gezler Garzuly

Sharing and learning with mentor, Maria Gezler Garzuly is a powerful, would-nourishing experience.

I met Maria in May of 2018. I was participating in a Hungary/Canada symposium at Kecskemet Ceramics Institute on the theme of Muscle Memory facilitated and invited by Mimi Kokai. There were seven Canadians and seven Hungarians, and we were working very hard to get our exhibition pieces ready within the one-month time allotted. I noticed this tall, yet spritely elderly woman with a lovely blue apron working to glaze a number of large stone-like objects near the gas kilns. I was curious, but Maria was frantic, working with extreme focus and tenacity. Two days later, Maria came to me, and she asked me about myself, and she shared about herself, her life, her work, and her family. We found a natural connection through our mutual love for classical music. I had begun to explore photography on porcelain prior to meeting Maria. A few days later, Maria invited me to come and study with her in her workshop to learn about image transfer and screen-printing. Covid happened, and five and a half years later, October 2023, the universe opened a doorway — Maria’s invitational course aligned directly with the end of my residency at Cill Rialaig in Ireland. I knew it was meant to be. The week was a massive adrenaline shot to my professional development, and a gift that I am so grateful to have received.

Nine women came together under one roof and drank fully of the wisdom, knowledge and expertise of Maria. We began, unexpectedly for me, with printing on glass, and suddenly I was a multimedia ceramics/glass artist! We each chose an image and made our own 8” x 10” silk screens from scratch – stretching the fabric over the frames, and learning under Maria’s careful instruction the magic of emulsification, light and image transfer. Maria taught us that there is no limit to what we can achieve, except for our own imaginations. She also taught me not to rush forward, to be patient, to be precise and to honour accuracy while at the same time allow for spontaneity. The joy of watching Maria create a new work from a shattered set of shards is something I will never forget.

I chose to work with an Irish block print image that was reminiscent of the landscape that seeped into my soul in the south of Ireland. Others brought their existing screens, six of the students are repeat apprentices under Maria’s tutelage. Each shared their images, and the collective ingenuity of the group was also a great learning opportunity. My creative taps are bursting with ideas to explore when I return, many years-worth of inquiry in the studio await me.

We also spent several evenings sharing our creative journeys on the big screen over palinka (vodka-like plum schnapps that is a local specialty). Maria offered us an overview of Hungarian ceramic artists and her work, I shared my work with image on clay, others shared about their life and work, including administrator, Kitti Antel, and our last guest, the mentor starting a workshop the following week, David Binns from Wales, illuminated us with his impressive research, creation and “green” recycling industry glass/ceramic work.

I had two days at the end of the course, and the warmth and openness of the group did not let me down. A fellow student from Austria offered to drive me to Maria’s hometown of Szombathely, the oldest city in Hungary, settled by the Romans in the 2nd century. Five of us arrived in virtual tandem, and spent a rare and enraptured afternoon at the Szombathely Keptar, revelling in Maria’s solo retrospective exhibition, Drama in the Garden. Maria has donated the works to the museum, and this is to become a permanent exhibition – the culmination of a lifetime of love, passion, loss, pain, curiosity, joy, rendered through Maria’s lens and life experience. Words are not enough.

We were then treated by Maria to a visit in her home and her studio, stories of her family, of the war and of the Revolution. Maria’s generosity and hospitality is overwhelming.

I am honoured to have eight new friends and colleagues in clay, and to glimpse but a fraction of the genius of Maria Gezler Garzuly.

I would like to thank the Ontario Arts Council for supporting in part, my participation in the workshop with Maria Gezler Garzuly in Kecskement, Hungary.

IRELAND: Cill Rialaig, & Much More!

Cill Rialaig is a miracle of a place on the southwestern cliffs of county Kerry in Ireland. It was born out of the will power and vision of 80-year-old Noelle Campbell-Sharp who formed a conservation committee and renovated eight 1790 pre-famine cottages thirty years ago. Noelle is a force of nature unto herself – a former magazine media mogul, she is dedicated to the over 6000 artists who have donned the doors of Cill Rialaig. I have had the privilege to stay in one such cottage with the best view of the cliffs, and a generous skylit studio space for the past two weeks. The people of Kerry are warm a kindly folk. While I have spent much time in silent solitude, wifi-free, reading, writing and beginning to hone my 2D painting skills with acrylics – I have also enjoyed getting to know a handful of kindred spirits here, perhaps a third to half of the artists who rotate through the cottages, and formed friendships quickly and with ease.

The highlight of my time here was taking advantage of a glorious sunny day, the stars aligning, and heading out for four and a half hours with a local archeologist in search of 5000 year-old petroglyphs. She took us to a spot that she knew well, and we easily found a dozen or so fairly stunning examples of rock art on the boulder strewn meadows of Glenbeigh, about an hour’s drive north. Then she asked us (I was with two American artists at the retreat) to wander about and find petroglyphs. And I did! I discovered a rock that had not been registered or recorded before. It’s a significant finding, with little to no lichens, which means that the peat had recently cleared from its surface. My eye counted at least eight circles and a straight line joining a few of them, concentric and small stacked “figure-8-like” chiselled markings within larger circles. Our guide was taken aback, as no visitor had ever discovered new rock art before. She contacted me the next day to get my particulars and my photographs for the national monument registry. I have truly left my mark in Ireland!

I have struggled with a sense of insecurity – and it was virtually impossible to break free from the drive to render the land with paint – but once I let go of the urgency to create something with a semblance of realism, I was able to flow with my true heart’s calling, abstraction, and then overlay the works with sand-paintings of the petroglyphs, actual transcriptions from my photographs.

Another highlight has been getting to know Stephen and Alexis O’Connell – a couple of production potters who set themselves up a mere four years ago, and are working full-time to supply a few Micheline star restaurants and chefs in Ireland. They work with ash and minerals making subtle minimalist work that appears to be atmospherically fired, yet brilliantly all fired in electric kilns! We had a couple of great visits and found that, yet again, the world is a tiny vessel indeed: Stephen was in Delhi last year and was guided in his pursuits by my former mentor, Mini Singh! Alexis is from Australia, all sorts of points of connection, and many shared values. Good people.

Stephen and Alexis O’Connell @ Fermoyle Pottery

When I felt as if I had put in a day’s work in the studio, and rain was not driving down on my skylights, I rewarded myself with a little excursion to see some local ruin or small town, or to take in the salt air of the sea. I was gifted many angels on my journey – artists who know the land well who guided me to find the ancient monastery ruins, the standing stones, and literally gave me the lay of the land. I am thrilled to find myself in the global communications capital of the 19th century, where the first transatlantic cables made contact with Heart’s Content, Newfoundland the 1850’s. I walked the shores of the cable stations and my heart leapt to be filled with the scent of the Atlantic – the wind whipping through every nook and cranny of its cragged landscape. I couldn’t help recall my time growing up in New Brunswick and all the times we ventured to the coast. There is a real sense of home, but not home. The small mountains with sheep grazing within the confines of their respective stone fences take me back to when I was a wee lass, and our family lived in Edinburgh for a year. However, the glory of these glens, cliffs, islands and rockface are like nothing I have experienced before. Today the power of the ocean reared its fierce fury against our cliffs – I’m going to estimate the spray reaching over 40 feet!

Before I came south to Kerry, Ali and I covered a lot of ground in Belfast (warmly received by fellow ceramic artist, Michael Moore); the Antrim Coast (welcomed by our new Trinidad friends, Pat Mohammed and Rex Dixon in their seaside home); we visited the UNESCO site, the Giant Causeway, and its impossible basalt stone formations, walked the forests, and gallery hopped in Dublin on our 25th wedding anniversary. Ali also spontaneously stopped in Linsburn for the International Festival of Linen – modelled after the one in Quebec where I showed a few years ago, Biennale International du Lin de Pont Neuf. I connected with many people there and took in the deep history of the place. I am working on a textile piece that I will send back to be part of the 2025 group project – the Longest Linen Tablecloth in the world, sewing my ancestors into the tapestry of their homeland. We did visit Armagh, from whence the McMenemy’s hail, and I have many leads to follow up to find out more. We ended up having a lovely connection with the guide at St. Patrick’s Cathedral, and wandered into the city’s annual Cider Festival, to take in live music and all-round top-notch people watching. We took the train to Kilkenny and met Tina Byrne at her recently established ceramics residency, Strata – and have bookmarked this piece of heaven as a place to return to as well.

The trip has been life-changing. Something in me feels more grounded and connected to a sense of where I came from, the land my mother’s ancestors would have toiled. I feel like a spec of sand on the beach of Ballenskelligs, one of many trillion, but all part of one.

I would like to acknowledge the support of the Ontario Arts Council in making this dream a reality.

AGO Review of Reclaimed: Indo-Caribbean HerStories

In her mixed-media ceramics-based exhibition, Heidi McKenzie enshrines collective memory

By Simone Aziga

Indo-Caribbean herstory at the Gardiner Museum

In her mixed-media ceramics-based exhibition, Heidi McKenzie enshrines collective memory

By Simone Aziga

Heidi McKenzie. Bangle, 2023. Stoneware, porcelain drybrush, glaze, silver acrylic pen. 18" x 26" x 8". Photo: Toni Hafkenshied.

Some stories are told and re-told, yet still not widely known as they should be. In her solo exhibition at the Gardiner Museum, Heidi McKenzie aims to change that for Indo-Caribbean women, bringing centuries-old herstories into focus through a feminist lens. On view through August 30, McKenzie’s mixed-media, ceramic-based work is a record of the past and present lived experiences of Indo-Caribbean women from the mid-19th and early 20th centuries through to today. The Toronto-based artist is of mixed Indo-Trinidadian and Irish American heritage and explores themes of ancestry, race, migration, and decolonization through her practice.

Installation view of Reclaimed: Indo-Caribbean HerStories. Gardiner Museum, 2023. Photo: Toni Hafkenscheid

As explained in the exhibition, 1833 was the official end of the legal trade of enslaved people in the British Empire. This shift resulted in the rise of indentured labour in the British colonies, particularly among Indian people. Of the estimated half-million Indians who migrated to present-day nations such as Trinidad and Tobago, Guyana, Jamaica and more with the promise of a brighter future, it is further estimated that 20 percent of these indentured labourers were women. These women, sometimes widowed and often seeking refuge from situations in their homeland, came to be referred to as “coolie belles”. As featured in Reclaimed, they were photographed in archival studio photography and postcards of time, left nameless with little personal details. The ornate jewellery they wore in these photographs signified status, cultural expression, and currency. The jewellery “became associated initially with the labouring classes and, more recently, with craft-based ties to matrilineal heritage.” Indentured labour continued in the Caribbean into the early 20th century until 1917.

Installation view of Reclaimed: Indo-Caribbean HerStories. Gardiner Museum, 2023. Photo: Toni Hafkenscheid

With poetic sensitivity, Reclaimed connects these women through archival and family photographs to their descendants based in and around Toronto. Included and on view are “wall-mounted portraits on porcelain, lit from behind, depicting contemporary Indo-Caribbean women with portraits of a female ancestor; a collage of “coolie belles” on porcelain windowpanes, inspired by turn-of-the-century postcards and ephemera; and a series of abstract figurative sculptures that respond to the work, alongside select pieces of Indo-Indentureship silver jewellery.”

Heidi McKenzie. Coinage, 2023. stoneware, porcelain drybrush, steel stands. 56" x 16" x 2". Photo: Dale Roddick

“Following the ideas of cultural theorist Arielle Azoulay,” McKenzie explains in the exhibition, “my work engages the socio-political landscape of my Indo-Caribbean ancestors, purposefully shedding light on the under-represented stories of Indo-Caribbean women. The ‘coolie belle’ portraits were shot on glass plates by male colonial photographers and hand-processed. The postcards were exoticized and commodified for Western tourists at the turn of the last century, hardships erased. My process of transferring portraits to ceramic tile is an act of both reclamation and decolonization. The courage and defiance of these women uplifted their ‘new slave’ status, as they fought for better working conditions and increased wages. They wore their savings on their bodies, jewellery fashioned from their earnings. I also give voice through portraiture to us, we, the descendants of the ‘coolie women,’ to reclaim our herstories.”

Heidi McKenzie, Looking Back: No. 1, 2023. Ceramic pigment photo decals fired onto hand-rolled porcelain, cedar frame, hardware. 24" x 18" x 3". Photo: Dale Roddick.

The exhibition is also accompanied by a series of video herstories by contemporary Indo-Caribbean women: Lancelyn Rayman-Watters; Talisha Ramsaroop; Ramabai Espinet; Suzanne Narain; Kamala-Jean Gopie; Preeia Surajbali; LezLie Lee Kam; Shanta Saywack Maraj; Cheryl Khan and McKenzie.

Reclaimed: Indo-Caribbean HerStories is on view in the lobby of the Gardiner Museum until August 30.

Reclaimed: Indo-Caribbean HerStories

My solo exhibition Reclaimed: Indo-Caribbean HerStories is at on the main floor of the Gardiner Museum, May 4 - August 27. To view the opening remarks on May 3rd, view this link.

East wall, Main Floor, Gardiner Museum. All Images photo credit: Toni Hafkensheid.

CLICKTHE VIDEO HERSTORIES BELOW for 3-minute videos of each of the ten women locating themselves in the diaspora and telling us a story of their female ancestor.

Artist Statement

I grew up in Fredericton, New Brunswick, the daughter of an Indo-Trinidadian immigrant who married an Irish-American woman—a brown face in a sea of white. My lived experience propelled me to engage with issues of race, identity, and representation. I began working with sepia-toned, iron-oxide rich archival photography on ceramic, rendering my father’s life and telling the stories of his ancestors. I persisted in using ceramic material in the production process, fusing coloured ceramic pigments onto hand-rolled porcelain.

Following the ideas of cultural theorist Arielle Azoulay, my work engages the socio-political landscape of my Indo-Caribbean ancestors, purposefully shedding light on the under-represented stories of Indo-Caribbean women. The “coolie belle” portraits were shot on glass plates by male colonial photographers and hand-processed. The postcards were exoticized and commodified for Western tourists at the turn of the last century, hardships erased. My process of transferring portraits to ceramic tile is an act of both reclamation and decolonization. The courage and defiance of these women uplifted their “new slave” status. They wore their savings on their bodies, jewellery fashioned from their earnings. I also give voice through portraiture to us, we, the descendants of the “coolie women,” to reclaim our herstories.

This panel discussion and community feedback session was recorded live on June 14th at the Gardiner Museum. Moderated by Alissa Trotz, U of T, and presented by Ramabai Espinet, U of T, Nalini Mohabir, Concordia, Joy Mahabir, Suffolk College, New York

Curatorial Statement, Sequoia Miller

Stories of Indian migrants who came to work on Caribbean plantations from the 1830s onward are often little-known. Toronto-based artist Heidi McKenzie explores the stories of Indo-Caribbean women and their descendants in Canada, including her own family, by reconsidering archival imagery and traditional jewellery forms through the lens of photography on translucent porcelain.

The end of the legal trade in enslaved people in the British Empire in 1833 prompted the immediate rise of indentured labour, particularly among people from India, in the Caribbean. An estimated half-million Indians migrated, often under dubious circumstances, to the plantations of the British colonies where they worked alongside formerly enslaved people of African descent. Among these, scholars estimate up to 20 percent were women, often widows or others escaping untenable situations. Archival studio photography from the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries documents these women, showing them bedecked with ornate, layered jewellery. Worn to assert status, as cultural expression, and as a form of currency, such jewellery became associated initially with the labouring classes and, more recently, with craft-based ties to matrilineal heritage.

Reclaimed: Indo-Caribbean HerStories takes inspiration from archival and family images to explore how descendants of “coolie belles” in Canada today connect to stories of their matrilineal ancestors. While clear documentation exists for some women, the archive is scant for many, prompting speculative or artistic ruminations on how traditions and identities are both passed down and created. The three primary elements of the installation—ceramic sculptures viewed alongside historical jewellery; contemporary portraits printed on translucent porcelain; and archival images on porcelain suspended in frames—use a feminist lens to explore these stories in different ways.

Part of the Scotiabank CONTACT Photography Festival, this exhibition highlights the complex, longstanding, and often unpredictable interplay between ceramics and photography.

I would like to acknowledge the support of the City of Toronto.

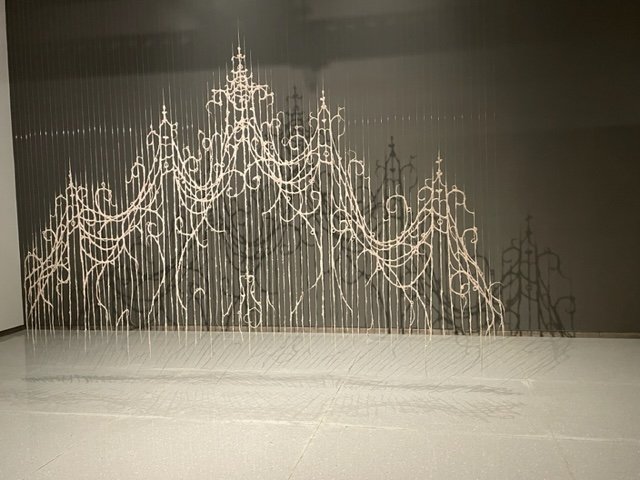

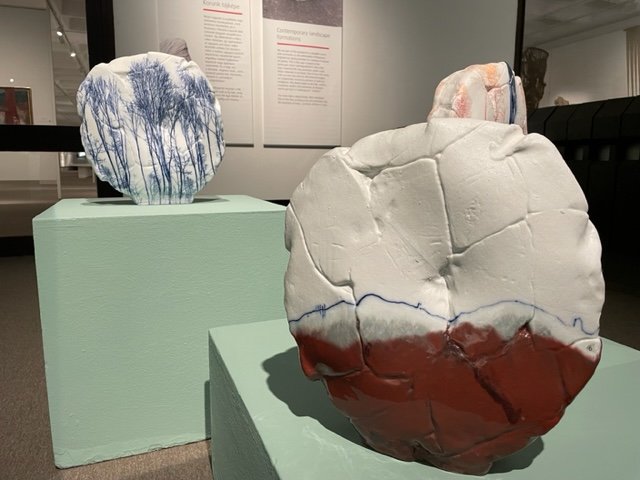

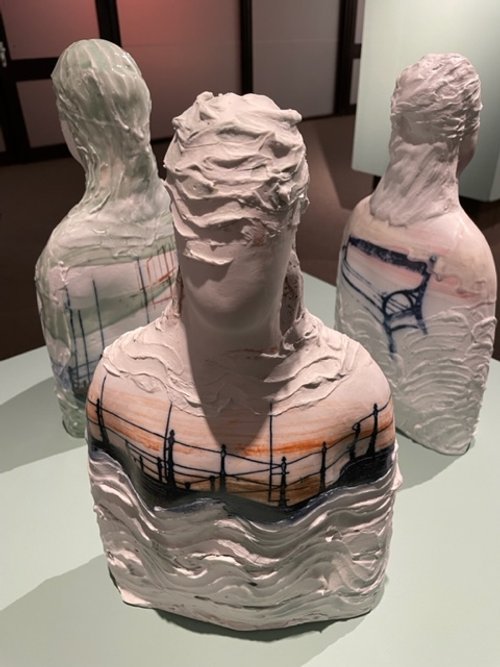

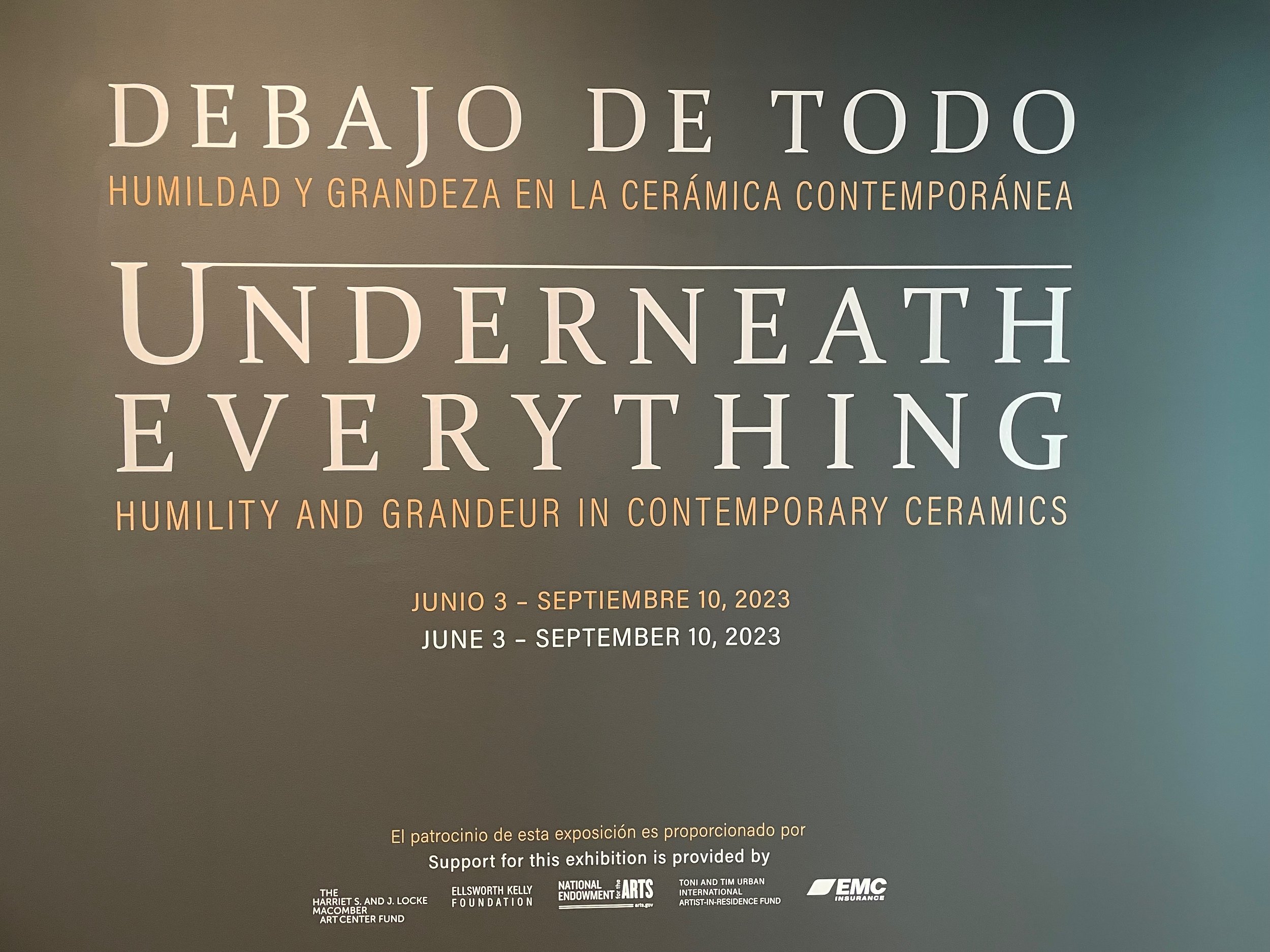

Underneath Everything: Grandeur & Humility in Contemporary Ceramic Arts

I am humbled to have been invited by curator, Mia Laufer at the Des Moines Arts Centre, Iowa, and to have my work, Division, exhibited with this artist list: Ai WeiWei, Katayoun Amjadi, Eliza Au, Sally Binard, Paul Briggs, Candice J. Davis, Edmund de Waal, CBE, Theaster Gates, Donté K. Hayes, Simone Leigh, Ingrid Lilligren, Anina Major, Heidi McKenzie, Magdalene A.N. Odundo, DBE, Vick Quezada, Ibrahim Said, Rae Stern, and Ehren Tool

“Clay is the humblest of materials, it is underneath everything...You can manipulate of world with clay.”

IM Pei Gallery - second part of the exhibition

The main gallery of Underneath Everything

Migrations: The Heart of Unusual Stories

Originally published in June/July/August 2023 issue of Ceramics Monthly pages 51-56 . http://www.ceramicsmonthly.org . Copyright, The American Ceramic Society. Reprinted with permission.

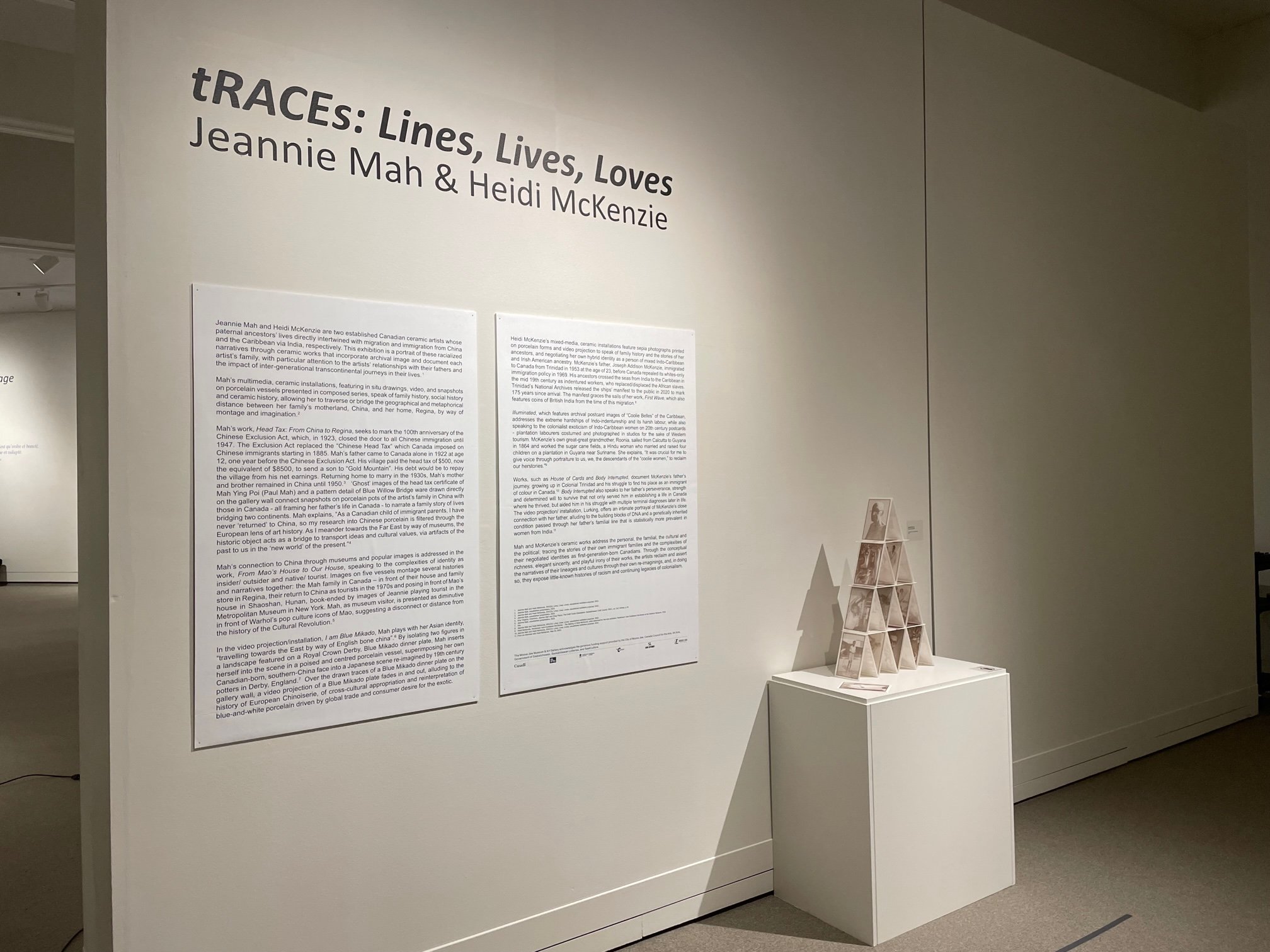

Read MoretRaces: Lines, Lives, Loves

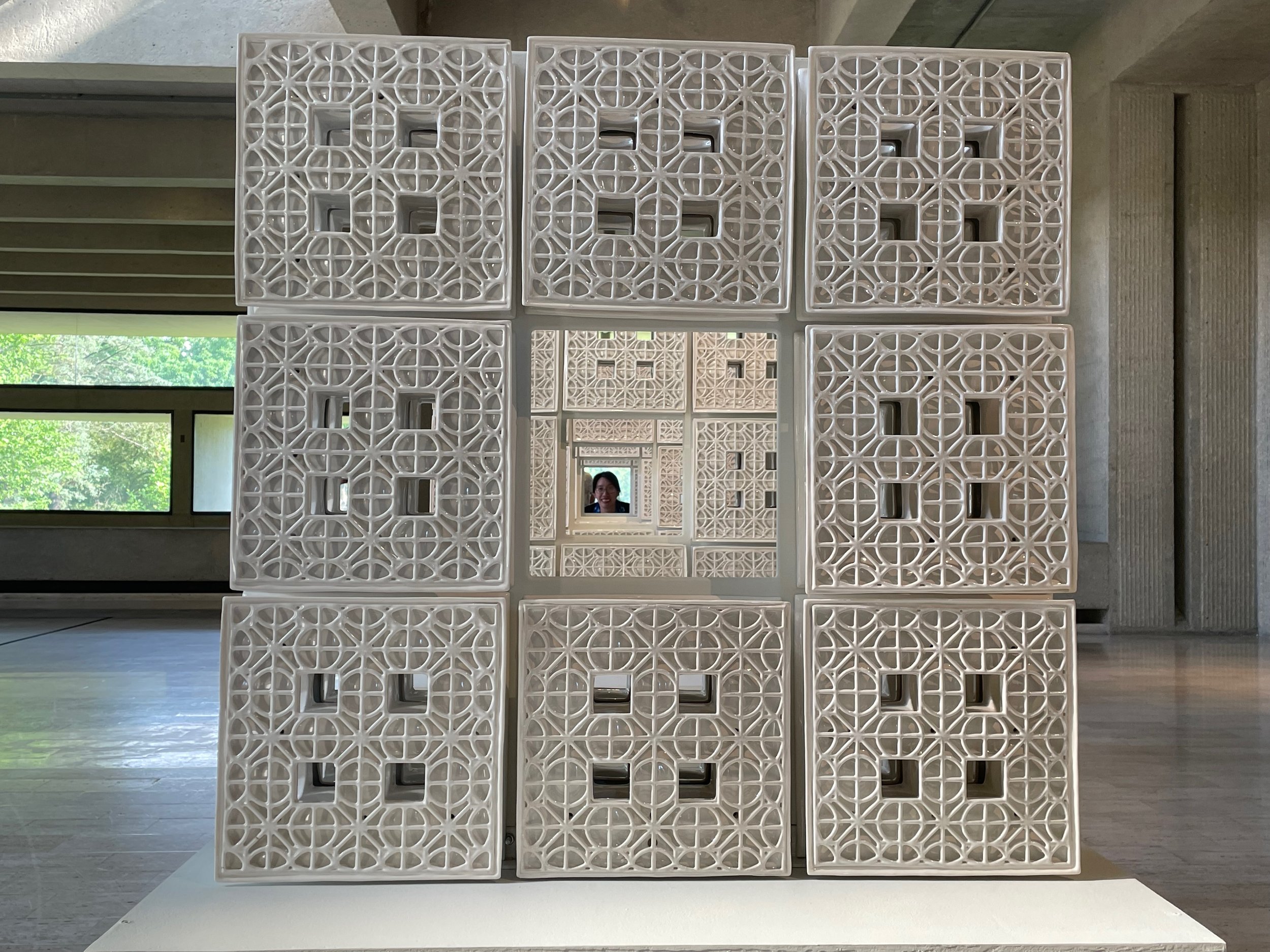

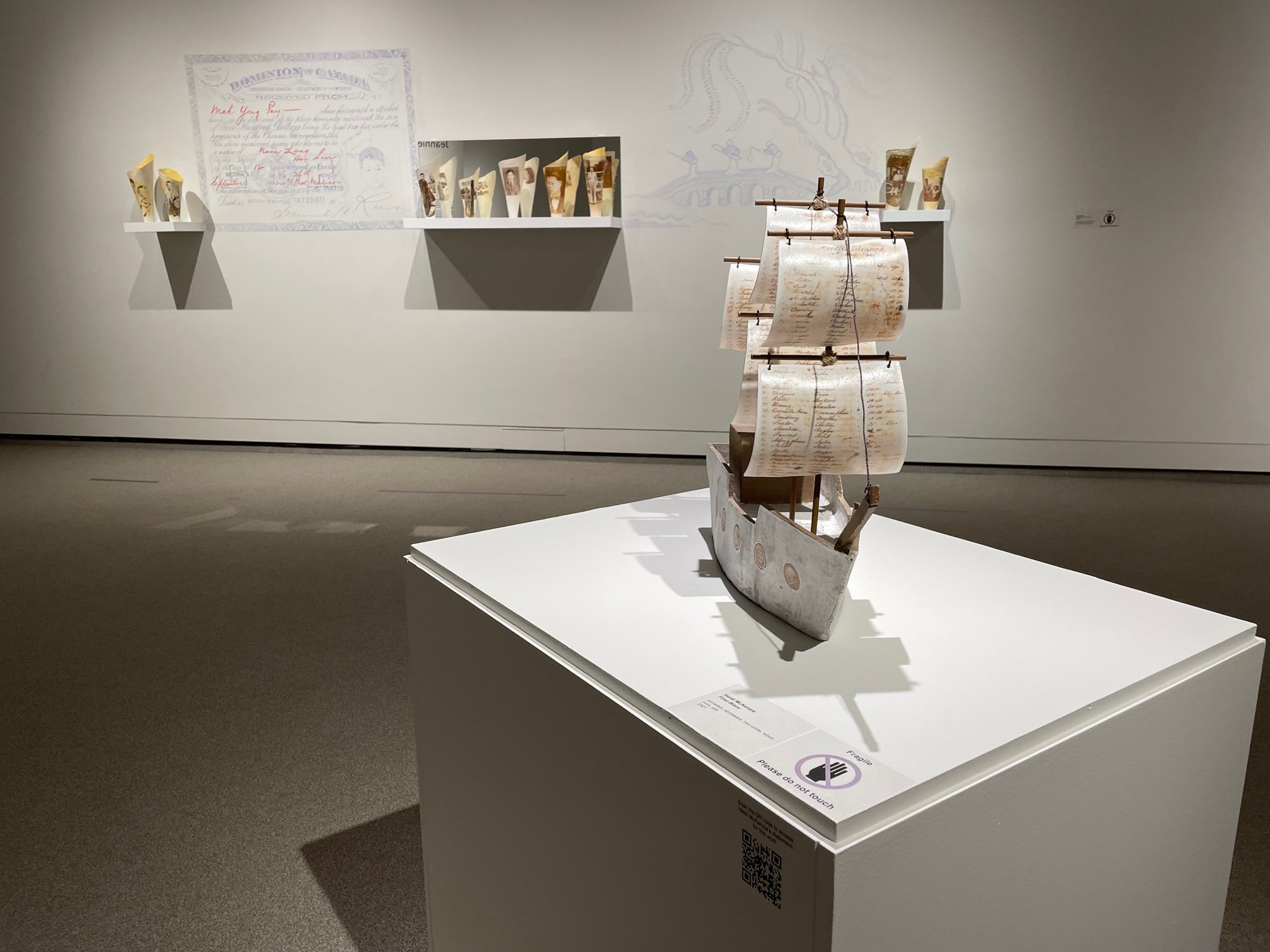

When Jennifer McRorie, Curator at the Moosejaw Museum and Art Gallery called and asked if I knew Jeannie Mah and was I interested in a two-person show, I didn’t hesitate. Jeannie and I had been scheming to do a show around our father’s as daughters of immigrants. The exhibition opened May 26th and runs until September 3, 2023 concurrently with by solo show, Brick by Brick: Absence vs Presence and Jeannie’s solo show, Invitation au Voyage.

Jeannie Mah, Heidi McKenzie with First Wave (foreground) and Head Tax (background)

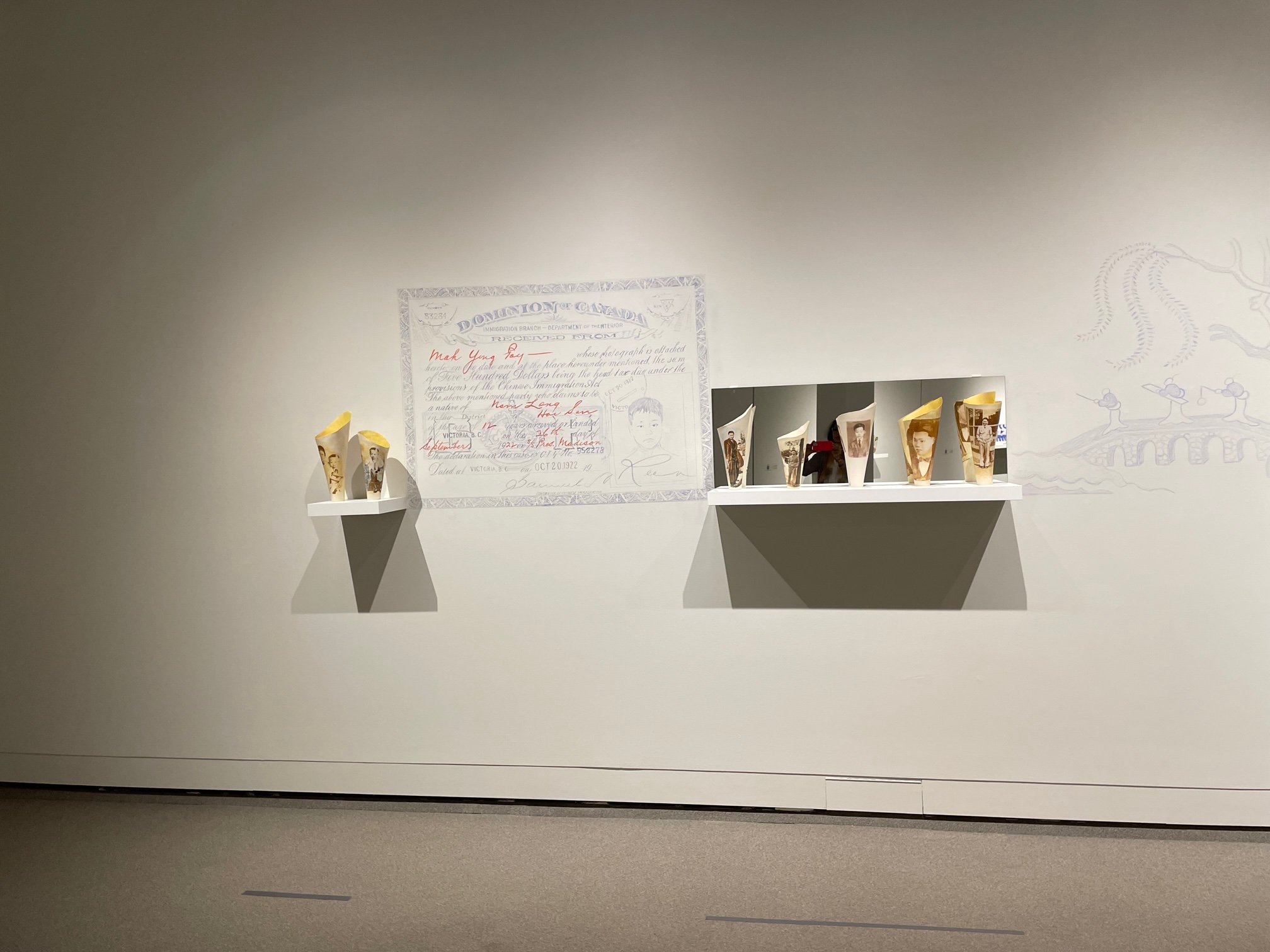

Jeannie Mah and Heidi McKenzie are two established Canadian ceramic artists whose paternal ancestors’ lives directly intertwined with migration and immigration from China and the Caribbean via India, respectively. This exhibition is a portrait of these racialized narratives through ceramic works that incorporate archival image and document each artist’s family, with particular attention to the artists relationships with their fathers and the impact of intergenerational transcontinental journeys in their lives.

Mah’s multimedia, ceramic installations, featuring in situ drawings, video, and snapshots on porcelain vessels presented in composed series, speak of family history, social history and ceramic history, allowing her to traverse or bridge the geographical and metaphorical distance between her family’s motherland, China, and her home, Regina, by way of montage and imagination.

Mah’s work, Head Tax, seeks to mark the 100th anniversary of the Chinese Exclusion Act, which, in 1923, closed the door to all Chinese immigration until 1947. The Exclusion Act replaced the “Chinese Head Tax” which Canada imposed on Chinese immigrants starting in 1885. Mah’s father came to Canada alone in 1922 at age 12, one year before the Chinese Exclusion Act. His village paid the head tax of $500, now the equivalent of $8500, to send a son to “Gold Mountain”. His debt would be to repay the village from his net earnings. Returning home to marry in the 1930s, Mah’s mother and brother remained in China until 1950. ‘Ghost' images of Paul Mah’s (Mah Ying Poi) head tax certificate and a pattern detail of Blue Willow Bridge ware drawn directly on the gallery wall, ‘ghost images connect snapshots on porcelain pots of the artist’s family in China with those in Canada - all framing her father’s life in Canada, narrating a family story of lives bridging two continents. Mah explains, “As a Canadian child of immigrant parents, I have never ‘returned’ to China, so my research into Chinese porcelain is filtered through the European lens of art history. As I meander towards the Far East by way of museums, the historic object acts as a bridge to transport ideas and cultural values, via artifacts of the past to us in the ‘new world’ of the present.”

Mah‘s connection to China through museums and popular images is addressed in the work, From Mao’s House to Our House, speaking to the complexities of identity as insider/ outsider and native/ tourist. Images on five vessels montage several histories and narratives together: the Mah family in Canada – in front of their house and family store in Regina, their return to China as tourists in the 1970s and posing in front of Mao’s house in Shaoshan, Hunan. These images are flanked by Jeannie playing tourist in the Metropolitan Museum in New York, on both ends. Mah, as museum visitor, is presented as diminutive in front of Warhol’s pop culture icons of Mao, suggesting a disconnect or distance from the history of the Cultural Revolution.

In the video projection/installation, I am Blue Mikado, Mah plays with her Asian identity, “travelling towards the East by way of English bone china”. By isolating two figures in a landscape featured on a Royal Crown Derby, Blue Mikado dinner plate, Mah inserts herself into the scene in a poised and centred porcelain vessel, superimposing her own Canadian-born, southern-China face into a Japanese scene re-imagined by 19th century potters in Derby, England. In the drawn traces of a Blue Mikado dinner plate on the gallery wall and an overlaid video projection that fades in and out, Mah alludes to the history of European Chinoiserie, of cross-cultural appropriation and reinterpretation of blue-and-white porcelain driven by global trade and consumer desire for the exotic.

Heidi McKenzie’s mixed-media, ceramic installations feature sepia photographs printed on porcelain forms and video projection to speak of family history and the stories of her ancestors, and negotiating her own hybrid identity as a person of mixed Indo-Caribbean and Irish American ancestry. McKenzie’s father, Joseph Addison McKenzie, immigrated to Canada from Trinidad in 1953 at the age of 23, before Canada repealed its whites-only immigration policy in 1969. His ancestors crossed the seas from India to the Caribbean in the mid 19th century as indentured workers, who replaced/displaced the African slaves. Trinidad’s National Archives released the ships’ manifest to the public in 2020 to mark 175 years since arrival. The manifest graces the sails of her work, First Wave, which also features coins of British India from the time of this migration.

Illuminated, which features archival postcard images of “Coolie Belles” of the Caribbean, addresses the extreme hardships of Indo-indentureship and its harsh labour, while also speaking to the colonialist exoticism of Indo-Caribbean women on 20th century postcards - plantation labourers costumed and photographed in studios for the sake of Western tourism. McKenzie’s own great-great grandmother, Roonia, sailed from Calcutta to Guyana in 1864 and worked the sugar cane fields, a Hindu woman who married and raised four children on a plantation in Guyana near Suriname. She explains, “It was crucial for me to give voice through portraiture to us, we, the descendants of the “coolie women,” to reclaim our herstories.”

Works, such as House of Cards and Body Interrupted, document McKenzie’s father’s journey, growing up in Colonial Trinidad and his struggle to find his place as an immigrant of colour in Canada. Body Interrupted also speaks to her father’s perseverance, strength and determined will to survive that not only served him in establishing a life in Canada where he thrived, but aided him in his struggle with multiple terminal diagnoses later in life. The video projection/ installation, Lurking, offers an intimate portrayal of McKenzie’s close connection with her father, alluding to the building blocks of DNA and a genetically inherited condition passed through her father’s familial line that is statistically more prevalent in women from India.

Mah and McKenzie’s ceramic works address the personal, the familial, the cultural and the political, tracing the stories of their own immigrant families and the complexities of their negotiated identities as first-generation-born Canadians. Through the conceptual richness, elegant sincerity, and playful irony of their works, the artists reclaim and assert the narratives of their lineages and cultures through their own re-imaginings, and, in doing so, they expose little-known histories of racism and continuing legacies of colonialism.

2-minute video tour of the exhibition by Heidi McKenzie

OPENING RECEPTION: Gardiner RECLAIMED: Indo-Caribbean HerStories

My exhibition, over a year in the making from concept to creation, opened at the Gardiner Museum on May 3rd, 2023. The video of the remarks by Chief Curator, Sequoia Miller and myself below: